Terranes as Terrains: The Klamath Mountains Oregon Study¶

Contents

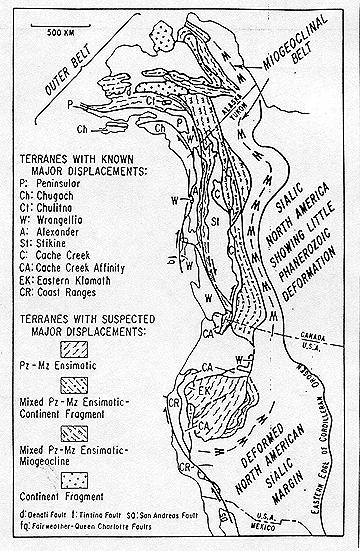

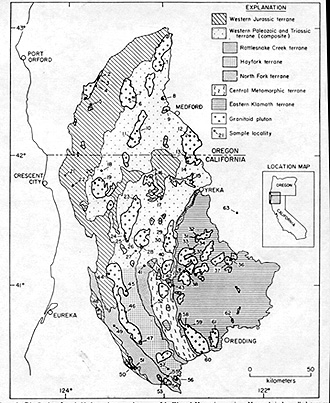

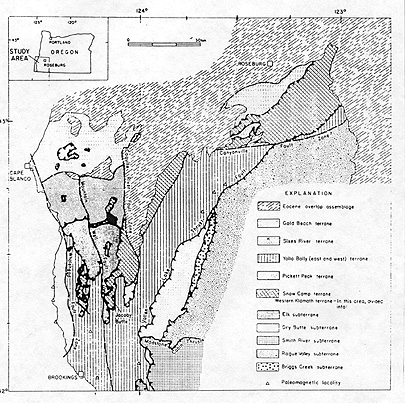

Following completion of Geomorphology from Space, this Tutorial’s prime writer (NMS) felt it would be instructive to further test the scientific utility of space imagery in analyzing the Earth�s landforms. He decided to conduct a pilot study of the Klamath Mountains of southwestern Oregon. The project was dubbed “Terranes as Terrains”. A terrane is a structural geology term that applies to large masses of rock - island arcs, subcontinental fragments of crust broken loose from tectonic plates, and other rock units embedded on a moving plate - that move along a spreading plate until they collide with the upside rock bodies at a subduction zone. Instead of going under in subduction, they are “welded” to the body (it may be a continent) and are thus added to a continental margin. The continent grows by accretion in this manner. Along western North America, where subduction has been active for hundreds of millions of years, there are many accreted terranes. Since each is generally different from the others in rock type and structural style, any landforms (terrains) imposed on individual terranes by the usual geomorphic processes are likely to be different (and probably thus distinguishable) from one another. This is the hypothesis that was tested. This first page expounds upon this background and shows the terrane makeup of both the West Coast (up to Alaska) and the Klamath Mountains (composed of many terranes).

Terranes as Terrains: The Klamath Mountains Oregon Study¶

As stated earlier in this Section, in 1985 the writer (NMS) initiated a research project while still at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, on which he continued to work until retiring from there in September, 1988. The supporting field effort was conducted while on sabbatical from Goddard between June and September of 1985. Although presented as a paper twice at professional meetings, this work remains unpublished because it is incomplete, with some open questions that would benefit from more research (unlikely, as funding is no longer accessible). However, the study did produce enough valid and meaningful results to justify putting forth the main data displays and analytical inferences as a model for the role of space imagery in a basic geoscience investigation.

The title of one of the presented papers, “Terranes as Terrains,” aptly summarizes the essence of the study. Freely translated, this refers to an attempt to determine whether certain kinds of geo-structural units (terranes) have distinctive and diagnostic landscape features (terrains) that make them easy to identify and that help us understand their origin, significance, and history. Three goals prompted this investigation:

To define and describe, qualitatively and quantitatively, the distinguishing geomorphic characteristics of known (previously mapped) terranes,

To determine whether individual terranes in a group have geomorphic signatures sufficiently different to permit us to recognize and separate them in aerial/space imagery, and to better delineate boundaries between terranes based on terrain differences,

To assess geomorphic information about terranes as clues to modes of emplacement and structural imprints.

The study applies morphometry to conventional and digital topographic databases and, wherever useful, Landsat/SPOT imagery.

The word “terrane” originally referred to “a crustal block, usually bounded by faults, with a geologic history distinct from histories of juxtaposed blocks of differing characteristics.” With the advent and acceptance of plate tectonic theory, users modified this concept with new insights into certain crustal blocks that they called “tectonostratigraphic”, “accreted”, or “suspect” terranes. In this view, they consider terranes to be diverse segments of crust that originated and developed often far from their present locations and over time traveled on a moving plate that converged with another plate, eventually colliding with a continental margin (along or within this second plate). There, they obducted (shoved onto) against the margin, rather than incompletely subducting (diving under) the second plate, thereby becoming accreted to that plate.

To give an example: masses such as microcontinents embedded in oceanic crust moving to a subduction zone may be unable to follow that crust downward and will be “scraped off” along thrust faults to emplace along the growing edge of the continental crust on the other plate. Or, a variant: if an island arc complex (e.g., Java, page 17-2) on the upper plate, above a subduction zone gets squeezed between two converging plates as a continent on the lower plate eventually reached the zone, much of the arc would be caught “in the crunch” to be driven on and welded to (accreted) the encroaching continent. The usual criteria for terrane recognition come from stratigraphic, structural, and paleomagnetic discontinuities between adjacent terranes. (For a quick review of relevant concepts, read pages 507 and following, and other parts of Chapter 18 in the introductory text: Physical Geology by B.J. Skinner and S.C. Porter, 1994, J. Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

Whereas in the thinking about growth of continents prior to the accreted terrane concepts, scientists explained complex geo-crustal units in the continents as consequences of fold-squeezing and fault transport during mountain building at geosynclinal sites, without much geographic displacement. Now, the new view recognizes distant site origins and relocations because of long movements on the “conveyor belts” of diverging plates. Continents thus grow by progressive accretion of numerous plates over time onto early cratonic nuclei. Since this concept first gained favor in the 1970s, geoscientists have recognized hundreds of terranes on all continents, in the sense that we re-interpreted older ideas about mapped geologic units to fit the terrane model. As an illustration of the terrane addition/continental growth version, consider this map that portrays a collage of the major terranes emplaced along the western margin of North America.

` <>`__17-16: To help you visualize what happens in continental breakup, drift, and reassembly, imagine (or you can actually do this) a spherical globe (like the one used in school to show the geography of the world), and ignore the actual continents on it. Place on it a piece of writing paper cut into a circle (about 4 inches in diameter). On the opposite side place another circular piece, perhaps of smaller diameter. Now, cut the paper into 5 to 6 individual pieces. Have each piece then slide across the face of the globe but in different directions, all moving simultaneously. Eventually, any of the pieces will meet the other smaller circular paper (assume it to stay fixed in place, but it could itself move as a unit or could be cut into several pieces that move [drift] apart - but this gets complicated even if it depicts a real possibility). As the spreading pieces of the first circular paper meet the second, they can be envisioned as lapping onto the second paper and becoming part of it, i.e., accreted by analogy onto what is a separate continent. In the accreted terrane paradigm, this process goes on continuously and involves many terrane units, large and small, repeated collisions, and eventual rupture of any continent that gets quite large. The continents, however, never get so large and stable that they cover the entire Earth, but instead, the spaces between them are made up of non-continental oceanic crust which is mainly basaltic lavas released to either side of mid-oceanic ridges that build up from lavas derived in the mantle; movement of these lavas away from the ridges leads to ocean “spreading” and drives plates against each other. `ANSWER <Sect17_answers.html#17-16>`__

Each of the named terranes is a unit which, after travelling some distance, “docked” against the paleo-North American continent, during some specific period. Most of the inner (continentward) units are progressively older than those outside, although thrust faulting can sometimes carry a younger unit over part of older ones. Each terrane maintains some internal structural integrity and consists of a series of stratigraphic units (formations), many not having counterparts in other nearby terranes. Those that do were likely deposited across boundaries after terrane emplacements.